Guest blog by Amber King.

This spring, after a large internal reorganization, Opower, the software company I work for based outside of Washington, DC, experimented with self-selection. Forty distributed engineers were allowed to choose for themselves what team and projects they would be working on for the next six months.

How did it work? Brilliantly! This is how we did it and what our engineers thought. If you’re interested in chatting more about self-selection or want help running self selection at your company, contact me (arking22@gmail.com) or Jesse Huth (jesse.huth@gmail.com).

What is Self-Selection?

Self-selection is an exercise that helps companies build high-performing teams by letting employees decide what to work on and who to work with. Sandy Mamoli and David Mole of Nomad8 developed the technique and wrote a book entitled: Creating Great Teams: How Self-Selection Lets People Excel. In it they describe a multi-round process by which large groups come together, share project details, self-select onto teams, and iterate until they’ve formed well-rounded, skilled teams. This has been done successfully for up to 30 agile teams, all in less than a day. At Opower, we piloted this on a much smaller scale, forming six teams in 2.5 hours across three geographies (California, Virginia, and the Ukraine).

How Do You Prepare For & Run a Self-Selection Event?

The self-selection process starts with preparation/socialization and ends with an iterative self-selection event where people make their team choices. For more details on what Opower did for each of the steps below, check out our blog post and lessons learned on Nomad8’s blog.

Prepare

- Understand self-selection: Read Creating Great Teams or Nomad8’s handy one-pager to learn more about the process.

- Develop a self-selection timeline: Start with the date you want to hold your self-selection event or your first sprint and work backwards.

- Socialize self-selection: Leave plenty of time for Q&A and coffees!

- Determine teams, leads, and projects: Work with your leads or even include the teams in making these decisions.

- Create team info sheets: Include name, mission, projects, and skills needed. Contact me if you’d like a copy of our template.

- Create individual info sheets: Include name, photo, skills, fun facts (optional) or go lean with just a photo. Contact me if you’d like a copy of our template.

- Develop rules: The most important rule will always be “Do what’s best for <your company>!”

- Find & train location captains: You’ll want knowledgeable boots on the ground in each location — or better yet, be co-located for the event!

- Final logistics: Make sure you have rooms, food, and everything printed.

Run the Event

A typical self-selection event lasts 4-8 hours. During each round, team members add their photos to the team they would like to be on. After each round, the teams are evaluated. Do they have enough people? Do they have the right skills? Did the teams follow all the rules? What gaps still need to be filled? The gaps are announced and another round starts. The event continues until all teams are filled, time runs out, or nothing changes for a couple of rounds.

Event Agenda

- 15 Mins | Gather & explain logistics

- 45-60 Mins | Team leads pitch their teams and answer questions

- 10 Mins | Self Selection: Round 1

- People place their individual info on teams

- Location Captains digitize the results as they happen

- 10 Mins | Round 1 Assessment

- Are any teams complete?

- Point out gaps

- 10 Mins | Self-selection: Round 2

- Repeat! Stop when teams are full, nothing is changing, or we run out of time

You may end the event with a few gaps in your teams. This is natural. Fill them with open hiring positions.

How Did It Work at Opower?

Three weeks is a really tight timeline, but having a timebox made the socializing part easier. The pain we felt NOT having set teams outweighed the potential pain of self-selection, so we were able to do this a lot faster.

Event Day

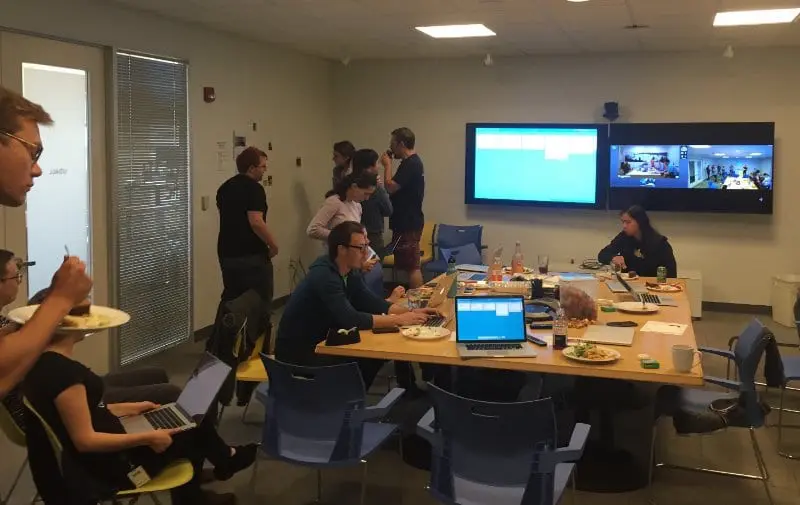

Our Selection Event took place on Friday, April 29. We made sure to order dinner for Ukraine, whose team stayed late for the event, lunch for Arlington, and breakfast for San Francisco, whose team came in early for the event. Having everyone connected at one time was key, even though it meant extra hours for portions of the tribe.

Self-Selection Results: Round-By-Round

Round 1: The results after round 1 were shocking. We expected to have maybe one out of six teams filled, but instead we had three teams filled, and two of them were fully co-located in Odessa, Ukraine. We still needed to staff three teams.

Round 2: Very little movement. We had two teams that were understaffed and one giant team with 11 people on it. We asked that group to go off on their own and figure out who would move. That worked terribly. Some intervention was needed.

Round 3: We had a full-fledged stalemate. We really only needed 1-2 people to move, but no one wanted to volunteer and be that person. It was clear that further rounds would not be successful unless we could break the stalemate. We turned the timer off and took a different approach.

Breaking the Stalemate: Our Engineering Director started a conversation, discussing everyone’s motivations for being on the over-staffed team (people loved that it was a full-stack team, they wanted to work with the leads, they wanted to do front-end work, etc). After one of our engineers spoke about wanting to work on a front-end solution that we call the Monitoring Dashboard, one of our Agile Program Managers realized that if we moved the Monitoring Dashboard work to one of the open teams, 1-2 engineers would happily come with it. After several sidebars, the matter was decided. The stalemate was over, we had our teams filled, and the event ended 30 minutes ahead of schedule!

Post-Event: We held a tribe leads meeting the Monday after the event to finalize teams and discuss any switch requests. We had no switch requests and very little to talk about in that meeting. Everyone was happy with their teams.

Feedback

The most amazing part of the event was the feedback we got afterwards. We sent a survey to gauge how the process worked and how happy people were on their new teams.

Almost 90% said they are happy with the team they ended up on, no one said they weren’t, and most of the people who chose “Other” were actually optimistic about their new teams.

We also asked “What primarily drove your self-selection choices?” We had thought that most people would choose teams based on the type of project they wanted to work on. But instead, as seen below, we found that most made their decision based on the best interests of the company as well as the people they wanted to work with.

One of the things we frequently hear from skeptics of this method are that “people will just work on what they want and leave the company high and dry.” As you can see here, a plurality (40%) of the respondents primarily chose their team based on the best interests of the company and then, secondarily, were driven by the people they would be working with (28%).

Happiness

It is important to note here the positive impact empowering employees to work with the people that they wanted to can have on worker happiness (Figure 1). Additionally, while it may seem that the type of work chosen was comparatively less important based on this data, our experience suggested that every team needs to have a critical mass of compelling work in order for everyone to come out moderately happy with the process,.

In the end, we came out of this experiment energized and optimistic that self-selection would end up being positive for the company. After reading the quote below from one of our engineers and seeing the data above, it truly felt amazing to know that we made our tribe happy with the process.

Could Self-Selection Work at Your Company?

Do you work at a company where people like to be told who they should work with and what they should work on? If so, this may not be the right technique for you.

All joking aside, I think any software company large enough to have several teams working toward a common set of goals could try this (i.e. you’re not working on client contracts that finish at different times).

Self-selection makes everyone nervous at first. (My initial issue with it was a sense that someone might feel like they were “picked last for the team”, which I’ve never heard of happening in any self-selection event and didn’t happen at Opower.) It’s important to take the time to work through everyone’s questions and decide ahead of time which risks you’re willing to live with. I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised!

Would you like help getting started or running your own self-selection event?

Self-selection is one of my favorite ways to make teams higher-performing. Contact me (arking22@gmail.com) or Jesse Huth (jesse.huth@gmail.com) for more information.

Special thank you to Amir Raminfar and Jesse Huth for not only being amazing event organizers, but for contributing and editing this post.

This content was originally posted on LinkedIn and is published on the LitheBlog with permission from Amber King.